National Geographic

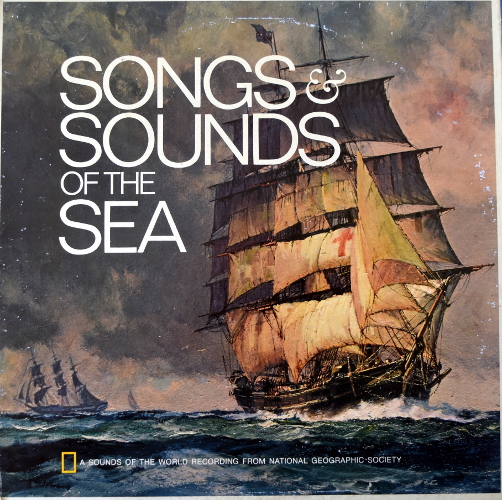

Songs and Sounds of the Sea LP

Rounding the horn meant raging seas and howling gales for the

JOLLY ROVING TAR

LP notes for the 1973 National Geographic LP:

Songs and Sounds of the Sea

All images are links to larger versions that include the captions from the sleeve.

Text and annotation by TONY SALETAN and JAMES A. COX

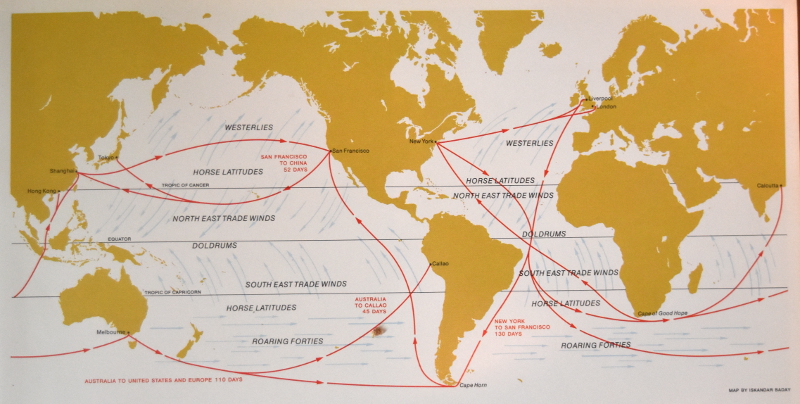

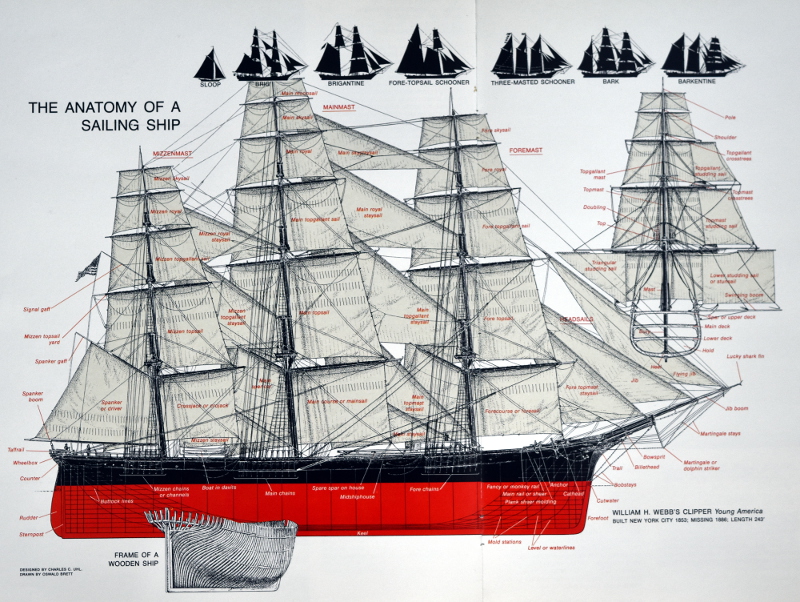

The fact that they had already given them skysails, and then crowded on other scraps of canvas they called moonrakers, should tell you something -- the clippers were rigged for speed. Their designers -- John W. Griffiths, William H. Webb, Samuel Hartt Pook, Donald McKay -- carved out knife-edged bows to slice through the rollers and fined down the lines to a thoroughbred trim. They flattened out the floors when they discovered that would pick up a knot or two. They sent masts towering 200 feet and more into the sky and stretched the yards out so far they scraped foam when the ships heeled. And they piled on canvas until it looked as if some sailor-turned-cowboy had roped a cumulus cloud.

At first a lot of people didn't think a ship so sharp would float, much less sail. When word got out that John Griffiths' 750-ton Rainbow, first of the extreme clippers, was going to be launched at last after more than two years at the yard of Smith & Dimon, a crowd of hundreds jammed the foot of East Fourth Street in New York City. They had come to see more than just another ship launching on that cold January morning in 1845, for there were rumors that the Rainbow's owners, Howland & Aspinwall, were afraid to let the water test her. And as they stood there waiting, puffing clouds of steam into the frosty air and shuffling their boots on the ice-mortared cobblestones, a grizzled old salt put into words what they were thinking. He had seen a ship built in Baltimore that wasn't anywhere near as sharp as this one, and when she hit the water, she kept on going -- down and under. That story ran through the crowd like wildfire.

Suddenly there was a bustle of activity in the yard, a gun was fired, and in an instant the air became electric with tension. The crowd surged forward. Sledges funked against the dogshores, and a hundred voices cried out in chorus: "There she goes!" A tremor, and she lurched perceptibly. Then, with a quickening, the ship slid down the ways and into the water with hardly a splash, dipped, righted herself, and moved away as gracefully as a swan. And nary a man there that cold, bright morning knew he had helped usher in the greatest era in the saga of the sailing ship.

No era is born overnight; the clipper ship did not emerge full-blown on the waves like Aphrodite in a scallop shell. You can trace her origins back to the rake-masted little schooners that "clipped" at 12 knots out of Chesapeake Bay shipyards during the American Revolution and the War of 1812 to play a deadly game of hit and run with British shipping. Peace brought stodgier ships with more capacious holds, but the sleek lines of the "Baltimore clippers" held on where speed counted -- in the opium runners haunting the coasts of China and the slavers bringing misery to America.

In 1818 Yankee ingenuity gave birth to the packet service -- ships that sailed the Atlantic on regular schedules, fully laden or not, fair weather or foul. Packet fever brought hot competition -- and the cry for more speed. But here the speed came not so much from the ships, built sturdy and full for passengers and cargo, as from the driving Yankee skippers who challenged nature on her own terms. "When a packet skipper got a favorable slant of wind," writes Capt. Alan Villiers, "he carried sail until it was impossible to go aloft and take it in. There it was and there it stayed, and the gale could do with it what it willed."

These two developing patterns in maritime America -- lean, race horse ships built for speed and hard-bitten captains ready to dare almost anything to get there first -- moved in roughly parallel courses until time and circumstance brought them together.

The time was the 1840's; the circumstance, the growing value of the China tea trade to both America and England. Tea was perishable, China was far away, and merchants willingly paid a premium for the first ship in port.

The fleetest craft on the seas -- Ann McKim, Natchez, Helena -- had already logged one record passage after another when the Rainbow joined the race in 1845. On her second trip out she dashed from New York to Macao and back in the fastest time yet, 6 months and 16 days, and John Land, her snowy-haired skipper, growled triumphantly, "The ship couldn't be built to beat the Rainbow."

He was wrong. Tea was one thing -- but gold was something else again. The frenzy that developed when glittering nuggets were discovered in California in 1848 -- and again in Australia in 1851 -- turned the tea races of the past into tea parties. Wild-eyed men waving their life's savings streamed into Boston and New York and Liverpool, all clamoring for a quick passage to the goldfields. Shipowners were happy to oblige.

Up and down the seafaring coasts saws and hammers rasped and banged day and night. And off the stocks came the beautiful ships, some of them built in only 60 days -- Mandarin, Flying Cloud, Comet, Stag Hound, Challenge, Sovereign of the Seas, Red Jacket, Lightning, Taeping, Ariel, Thermopylae, Cutty Sark....

The gold rushers and the tea merchants wanted speed, and often enough they got it. Capt. "Bully" Waterman set the pace. He drove the Sea Witch from Hong Kong to New York in 74 days 14 hours to set the world's first permanent sailing record, having already gained undying fame -- or notoriety -- in the Natchez, whose sailors claimed he nailed down the lines so the topsails couldn't be taken in, whatever the weather. More than one clipper logged over 400 miles in a day, reaching 22 knots in squall winds -- better than many steamers can do today.

Not all voyages were record makers. Many a proud ship limped into port six or seven months after sailing, canvas in tatters, masts and yard smashed into kindling. Others simply disappeared, leaving no trace.

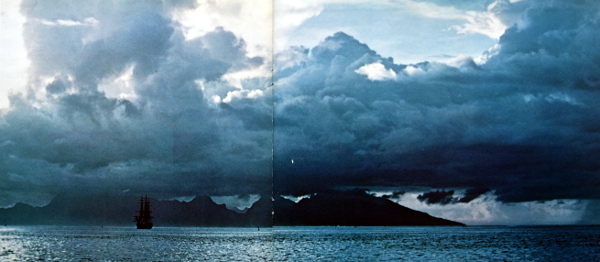

Gales, doldrums, treacherous seas, and perverse winds all bedeviled the tall ships. But most dreadful of all was the stretch of turbulent seas from "50 South to 50 South" -- the passage around the Horn.

To the ordinary seaman, as often as not a poor lubber who had been signed aboard by way of knockout drops in his drink and who had learned the sailor's trade dodging a burly mate's belaying pin, shipboard life was bad enough -- rancid food, a soggy bunk, and too little sleep, all for $8 a month. But rounding the Horn, a 1,390-foot headland that knows no peer in the relentless violence of the icy storms that wrack the waters off its bleak coast, was a torment conceived in a frozen hell.

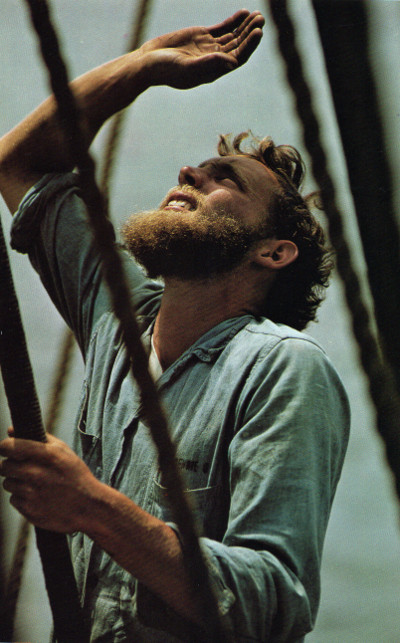

Crouching aloft in the reeling yards, his stomach playing tag with his backbone -- while the ship pitches and heaves in the gigantic seas, while the steely claws of gale and hale try to wrench him from his perch -- he struggles to bring in a sail frozen as hard as iron. Ice coats his hair and beard; the wind tears at his eyeballs; the nails rip off his blue fingers, and blood dribbles down the sail, freezing almost instantly. He stares at it stupidly -- feeling will return with a vengeance later. And if he makes it safely down to the deck, this time and all the other times, he'll have to take his meager satisfaction in the fact that he's a Cape Horner -- a lubber no more.

In spite of his misery, or maybe because of it, the clipperman willingly lent his voice to the lusty songs his mates sang as they leaned against the capstan bars or hauled in on the halyards -- the work went easier to the rhythm of a rousing chantey. And down below in the off watch, if a man could play a jolly tune on the fiddle or concertina, pluck a banjo, or sing a sweet sentimental ballad in a voice true and sweet, he would find his talent cherished.

For these were not really iron men, as legend would have it, but vulnerable creatures of flesh, bone, and sinew. Tough they were, and sometimes brutal, but under the horny exterior burned sparks of humor and tenderness -- their music gives them away. They held no poetic view of the sea, however; there are far more songs about coming home than about going out.

Although many of them hated the sea, they suffered when it became apparent that the twilight of an era was closing down on them. They saw their graceful ships smashed in the Civil War by the Alabama and other raiders. Later they saw them rotting in port while the squat, smoke-belching iron steamers stole their passengers and cargoes. The wind was free, and a tall ship leaning before it with the white bone in her teeth could outrun any steamer on the seas. But the wind was also capricious, and a plodding steamer doing a steady 8 knots could arrive as well as leave on schedule.

When they saw the Suez Canal opened for the benefit of the steamers -- that "dirty ditch" they called it -- they knew they were doomed. Proud ships that once had raced for glory, battling nature at her worst with canvas glued to the yards, were now reduced to hauling coal and guano until the sea pounded open their seams or they were hauled to the breaker's yard for their brass and copper fittings.

The wind still blows free, rustling the grass and quiet seaport graveyards where the old sailors sleep, stirring the waters under which so many others lie. But the tall ships are gone, their bones ground into dust on some lee shore or rotting away in the ooze of the ocean bed, all save a few relics lovingly preserved to remind us of the beauty of what had been.

Many of the songs have been saved, too, and some of the most rollicking music that ever pealed out over the sea has been re-created in this album. But more than a mere re-creation was involved. The songs were born to the accompaniment of the wind in the ship's rigging, and no recording studio far from the sea, however convenient, could hope to truly capture the sounds of a rousing chantey or a bright forecastle ballad.

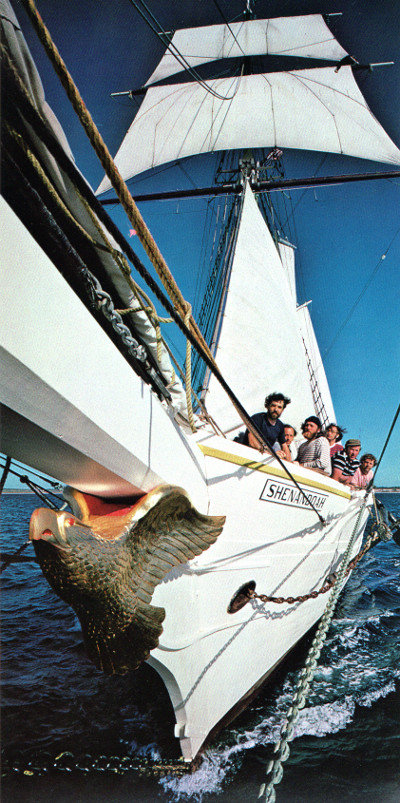

So it was that, to go back in time for one glorious moment, we gathered up our banjos, concertinas, penny whistles, and recording equipment and traveled to Vineyard Haven in Massachusetts to board Capt. Bob Douglas's extreme clipper schooner Shenandoah. A grand sight with her bright canvas sails and gilded eagle figurehead, she is the only square-topsail schooner still under American registry. Built to resemble as closely as possible the great ships of another era, she was launched in 1964. To walk her oiled pine decks is to step back into the past a hundred years.

Come aboard with us. Smell the hemp and tar, the unmistakable salty tang of the deep-sea. Watch the gray evening fog roll across the water and turn into glistening golden mist in the soft light of the kerosene lanterns. Listen to the hiss of the sea curling back from the slicing bow, the slow creaking of the sturdy timbers, the thrumming of Manila line stretched quivering taut, the groaning of the wind as it leans into bellied canvas. And against this magnificent orchestration hear the songs of the sea come alive once again, sung and played not with the quaintness of a musical performance, but in the style of the men who created them -- loud and lusty, broad and bawdy, or tender with the loneliness that only a sailor knows.

SIDE ONE

- ALONG THE PIER

- Early morning mist, pearl gray in the soft light of night receding, curls up from the dark waters of the harbor. On the far horizon a new sun surges aloft as flocks of hungry gulls rise to greet the day with raucous cries. It is a fine salty morning, a good time to walk down the cobbled streets of a 19th-century seaside town to the waterfront, where a wooden wall of stubby fishing boats, tub-bottomed merchantmen, and sleek clippers raises skyward a forest transplanted -- tall masts and tapering yards even now catching the sun sparkling with dew.

- Your footsteps echo on the heavy timbers of the pier, blending with the sound of the ships, the gulls, and the fresh-born day. But suddenly life springs up all around. From a ship weighing anchor in the harbor comes the clank of rusty chain and lusty voices bending to the old capstan chantey, Clear Away the Track, led by strong chanteyman Tony Barrand.

- A heavy horse cart rumbles by to the jingle of harness carrying the first cargo of the day to some quayside warehouse. Farther along the mole, a bearded seaman lounges against a weathered dolphin. Louis Killen, his well-worn concertina in hand, plays the lively jig Ten Penny Bit. Just ahead, the Dreadnought lies ready to sail. The sun is higher now, bright and warm. It's a fine day for heading out to sea.

- THE DREADNOUGHT

- The packet Dreadnought, pictured on the album cover, was built in 1853 in Newburyport, Massachusetts, for Capt. Samuel Samuels of the Red Cross Line. Although neither as sharp as the famous clippers of the area nor as swift as some of the other packets plying the Western ocean, as the Atlantic was called, the Dreadnought was famed for the fast passages she made under the "unceasing vigilance and splendid seamanship of her commander." She sometimes even beat the steamers on the New York-to-Liverpool run. She was wrecked rounding Cape Horn in 1869, and her crew was rescued only after 14 days adrift in open boats. The Dreadnought's song, one of the few surviving ballads dedicated to a particular ship, glistens with the pride the packet rats took in their hard-driving vessels. Cliff Haslam sings, with Jeff and Gerret Warner and Tony Saletan on the choruses.

- MONEY IN BOTH POCKETS

- After months at sea, the lonely sailorman yearned for the pleasures of the land. But he knew from experience that his welcome, whatever his shipboard dreams, would be a poor one if his pockets didn't jingle -- which perhaps explains the popularity of this Irish reel, played by the Boys of the Lough with Cathal McConnell on whistle, Aly Bain on fiddle, and Dave Richardson on mandolin.

- Irish music was no rarity on the old sailing ships, American as well as British, for many a fine lad made his way to Dublin or Cork, and then shipped out to see the world. As a matter of fact, many of the so-called forecastle songs, sung and played on American vessels during the off watch by sailors with little else in the way of entertainment, were variations of old Irish, English, or Scottish ballads, some of which may have originated in the Middle Ages. And from cotton ports of the American South, Negro work songs were taken to sea, adding yet another influence to the rhythm and style of the clippermen's chanteys and ballads.

- BLOW, YE WINDS

- 'Tis advertised in Boston, New York, and Buffalo, A hundred hearty sailors, a-whaling for to go...

- Michael Cooney, accompanied by his sparkling five string banjo, sings one of the best of the whaling songs. Blow, Ye Winds comes from an old English ballad concerning the adventures of a clever lady and an amorous knight. But the traditional sailor's words are straight from the heart of the whalerman's bitter experiences -- promises made on land usually differed radically from the harsh realities of life aboard a whale ship.

- BOSTON HARBOR

- The origin of this song, which was also called With A Big Bow Wow, remains a mystery, but the popularity it enjoyed during the 1860's is proof that some unknown lyricist succeeded in putting into words the feelings of many a man before the mast toward his hard-handed skipper. The tune itself was very common at the time, and provided the vehicle for a number of different sets of words. Joe Hickerson, who sings it here, has seen many a 19th-century song text carrying the note, "Air: With A Big Bow Wow." Jeff and Gerret Warner and Tony Saletan join in the choruses.

- JOLLY ROVING TAR

- For all the harshness of his lot at sea, Jack-tar often found life ashore somewhat less than idyllic. But he could find humor even his rapid fall, once his pay was spent, from honored "John" to scorned "Jack," just as a refrain in this lively forecastle ditty reveals:

When your money's gone,

It's the same old song,

Get up Jack! John sit down! - "I have heard this old tune many times," relates Tony Saletan, "but it touched me most deeply one night as the Shenandoah lay anchored in the still waters of Tarpaulin Cove near Martha's Vineyard. During the afternoon, fog had started to roll in and by evening it shrouded our vessel like a great gray blanket. On deck kerosene lanterns glowed in the swirling mist, while amidships a halo of yellow light marked the skylight over the main saloon. As I stood on the seemingly deserted deck, I could hear the lapping of waves against the hull, the dripping of condensation falling from the rigging, and the muffled moan of a distant foghorn.

- "Spying a shadowy figure at the stern, I made my way aft and as I approached the main saloon skylight, Jeff and Gerret Warner, with our crew below, struck up Jolly Roving Tar. It was as if I had been suddenly thrust into a time machine -- sent spinning back through the fog a hundred years or more. For some reason there slid into my mind a picture of two weathered gravestones that I had studied earlier in the day. They stood not far from the old lighthouse near the edge of the cove and they marked the graves of two men who had died at sea -- Capt. William Loring, 1788, and Capt. Eli Parnele, 1805.

- "The song was nearing its end when the other man, leaning on the rail and staring off into the fog, cleared his throat. Snatched back to the present I peered closely at him -- it was Capt. Bob Douglas, skipper of the Shenandoah, and a man of few words if ever there was one. But he spoke now. Gesturing toward the lighthouse, he said softly, 'I'll bet the captains are enjoying this.'"

- Here's the song that Jeff and Gerret recorded that evening. A fine version collected by their family from Lena Bourne "Grammy" Fish of Jaffrey, New Hampshire, who learned it years ago from an old whalerman.

- PATSY CAMPBELL

- On land, the traditional bodhraw, or one-headed drum, would provide the rhythm for this Irish reel of Michael Russell's writing. But dampness aboard ship would soon slack the skinhead's tautness and reduce its resonance to a soggy thunk. Seagoing drummers would therefore tell the beat by slapping it out on the top of a barrel or sea chest. Cathal McConnell and Robin Morton, Boys of the Lough, present this lively reel in the old way, with Cathal tootling the whistle and Robin "playing" a wooden plank.

- THE WHALE CATCHERS

- We tend to think of New England when it comes to whaling -- Nantucket, Martha's Vineyard, and New Bedford -- forgetting that other lands also have a heritage of chasing the great Leviathan to his watery lair. The Whale Catchers, sung here by Tony Barrand with John Roberts accompanying on concertina, was a favorite of British whalermen sailing out of Bermondsey, London, from Greenland Dock, as it is still called. Cast in the mold of the epic tale, the song re-creates the prayerful departure, the painful realism of frozen fingers and toes suffered in the bitter winds and cruel seas off Greenland, the successful hunt, and the joyful return home -- "Oh we'll make them lofty ale houses in Londontown to roar!"

- WHEAT IN THE EAR

- Bonnie Prince Charlie, the Stuart Pretender, inspired a Jacobite song that apparently was the rootstock for a singing game, a Virginia reel, and a weaving ceremony. It also served as a source for this delightful song of a sailor going back to sea, the young lass he is leaving behind, and how she'll grow and ripen while he's away. Gordon Bok plays the dulcet Portuguese laudo and sings whimsically.

Take her by the lily-white hand,

Lead her like a pigeon,

Make her dance to weevily-wheat,

And scatter her religion.

Wheat in the ear,

My true love's a posy blowin'.

Wheat in the ear,

I'm going back to sea.

Wheat in the ear,

I left you fit for sowin',

When I come back,

What a loaf of bread you'll be!

I don't want your weevily-wheat,

I don't want your barley

Want some flour and a half an hour,

To bake a cake for Charlie.

Tradin' boats a-goin' ashore,

Tradin' boats a-landin',

Tradin' boats a-goin' ashore,

All loaded down with brandy.

Weevily-wheat, my true love's a posy blowin'.

Weevily-wheat, I'm going back to sea.

Weevily-wheat, I left you fit for sowin',

When I come back,

What a loaf of bread you'll be!

Take her by the lily-white hand,

Lead her like a pigeon,

Make her dance to weevily-wheat,

And scatter her religion. - THE LITTLE BEGGAR MAN

- In the grim days before scurvy was known to stem from a lack of Vitamin C in the typical seagoing diet, British ships traditionally carried a fiddler whose duties included playing lively hornpipes to which the seamen had to dance -- the idea being that the stirring of their blood would prevent onset of the dread malady. For this reason perhaps, hornpipes have a peculiar ability to conjure up images of the days of sturdy wooden ships and booming canvas sails. Michael Cooney's light triplets on the five-string banjo decorate the melody of The Little Beggar Man, a hornpipe that gained favor in Ireland as the Red-haired Boy and in America as, oddly enough, There Was an Old Soldier and He Had a Wooden Leg.

- JOHNNY TODD

- The girl he left behind -- has there ever been a young sailor or soldier who didn't have the same worry: "Will she be true?" In the case of Johnny Todd, she wasn't; she married another sailor while he was far away at sea. Johnny's sad story ends with a piece of advice that only a very young sailor would accept as a solution to the problem: Marry her before you go.

- More cynical heads might see in this an invitation to graver problems, but such dour thoughts do nothing to diminish the pathos of Johnny's betrayed love, a common enough condition in any age. Louis Killen with his concertina sings and plays this old song of the sea, which lives on as the rhyme for a game children play in Liverpool, most storied of Britain's sailing ports.

- SAIL AWAY, LADIES

- This sprightly melody, played by Michael Cooney on his banjo, is a fine example of the truism that music can bridge all gaps, geographical and historical and sometimes even ethnic. Born as a sea song, it is been heard with new words in the southern mountains of the United States. Through the years, many a fiddler has sawed it out at country hoedowns. And, fitted with another set of words, it became a part of our history.

I got a letter from Shilo town,

Sail away, ladies, sail away,

Big St. Louie is a-burnin' down,

Sail away, ladies, sail away.

SIDE TWO

- THE DIAMOND

- So it's cheer up me lads, let your hearts never fail, for the bonny ship the Diamond goes a-fishin' for the whale.

- So goes the refrain of this fine old song, created early in the 1800's when the Diamond was one of the proudest ships in the British whaling fleet that scoured the frigid waters of the Greenland Sea. When the success of the whalers brought lean pickings there, the fleet moved on to richer hunting grounds in the Davis Strait, the strip of water between Greenland and Canada 200 to 500 miles wide that connects Baffin Bay with the Atlantic. Here, in 1830, disaster struck the Diamond, the Resolution, the Eliza Swan, and other ships of the fleet that were locked in the grinding jaws of packed ice. There was no way to escape, no rescue to be expected in this desolate area. Many brave seamen died of starvation and cold, perhaps even the man who first sang, in happier times, "so cheer up me lads, let your hearts never fail."

- John Roberts sings and plays the banjo here with Tony Barrand, David Jones, and Jeff and Gerret Warner in chorus.

- DEIL STICK THE MINISTER

- Converted to modern English, the title of this Shetland Islands' reel means "Devil Beat the Minister." There is no reason to assume that Shetland Islanders are less religious than other folk, but they do have a tradition that a minister aboard ship brings fisherman bad luck, which may account for the tune's popularity there. The song itself, which very likely was composed as a protest when the Church condemned fiddle music and the joys that went with it, is also known in other parts of Scotland and Ireland and was probably brought to the Shetlands by a homecoming seamen. Dave Richardson plays it here on his mandolin.

- RIO GRANDE

- Americans brought up on a diet of Western films might be forgiven for assuming that the only Rio Grande worth mentioning is the river marking the boundary between Mexico and the United States. Not so with the sailors of old, for this most popular of outward-bound chanteys refers to the faraway port of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil.

- Considered by some lovers of sea music to be the finest chantey of all, this rousing tune was sung by sailors all over the world with hardly any variation in the melody, but with many different sets of lyrics. Though some version said good-bye to the Bowery ladies, and others sprang from the California gold-rush days, the one sung here by Jeff Warner speaks the business at hand -- heaving around the capstan. American and British seamen, no linguists they, almost religiously mispronounced the foreign words and phrases they heard -- although often enough with comic intent. In this tradition, they always sang Rye-O rather than Ree-O as Jeff, Gerrett, Cliff Haslam, and Tony Saletan do here.

- OLD MOLLY HARE

- One thing serious students of the sea's musical past learn is never to be dogmatic in their assumptions. Words and music that were rarely written down were subject to much transformation and elaboration as they were passed from one performer to the next by ear and memory. And too, in truth, there was considerable honest borrowing going on as talented men tried to put wings on the lonely hours by offering their messmates something new. A snatch of chantey, for example, or a scrap of fiddle music, overheard from a passing vessel, could set an inspired balladeer to creating a new forecastle song.

- Old Molly Hare is one of the songs of dubious lineage. Popular belief holds that it is descended from an Irish tune called Mollie O'Hara, and there is no gainsaying similarity of titles. But a title is no more than a label by which one man identifies a set of notes or words he has heard and the song now known as Old Molly Hare is more likely the American version of the Scottish reel called Fairy Dance. On the other hand, however....

- Michael Cooney puts the debate to rest, at least temporarily, with his spirited banjo.

Special thanks go to my wife Cindy, who helped transcribe this lengthy document without enjoying one note of the music!

We welcome any suggestions, contributions, or questions. You send it, we'll consider using it. Help us spread the word. And the music. And thanks for visiting.